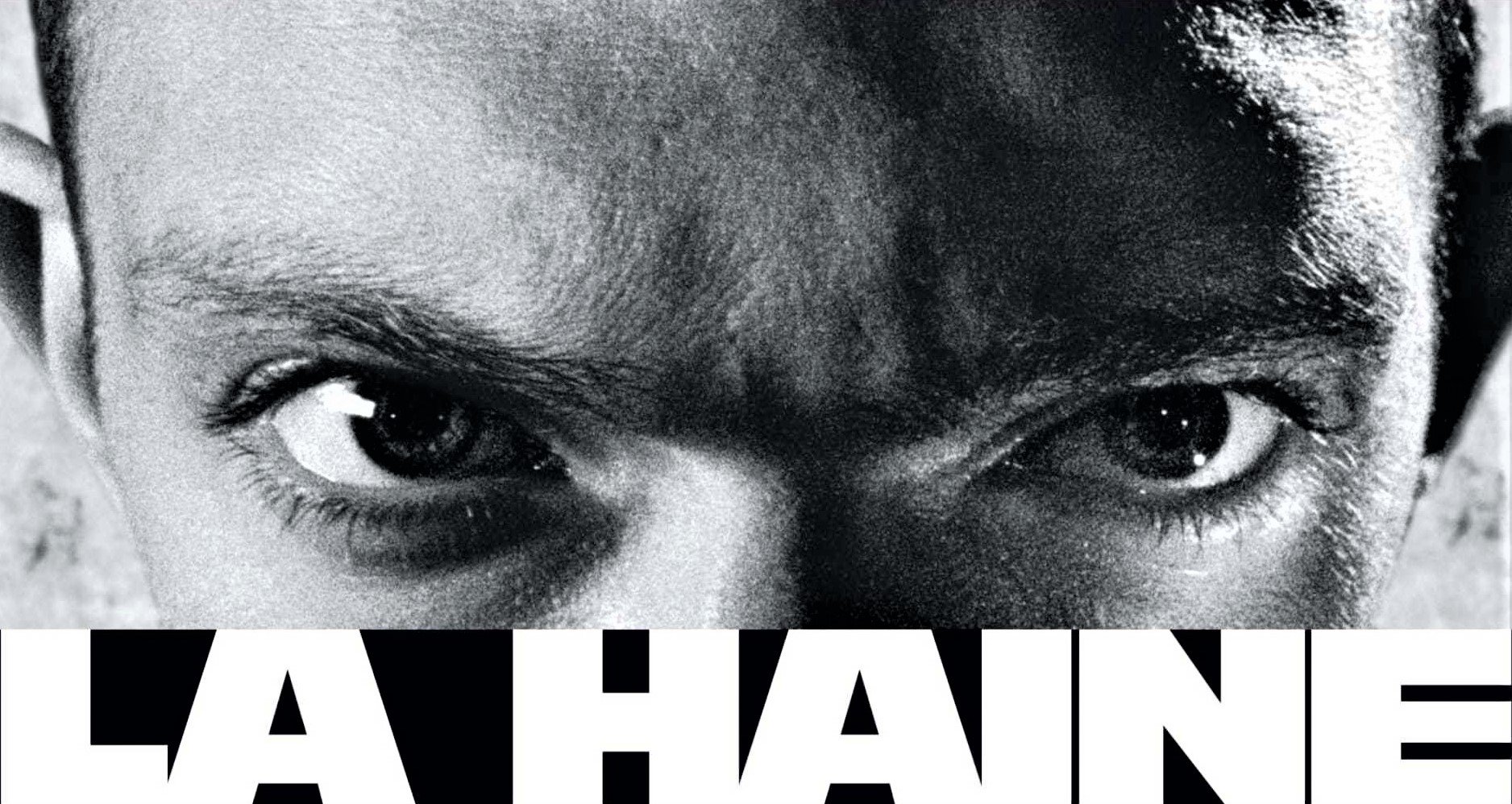

La Haine: Hatred

The marginalized captured their voice.

French lifestyle has rarely been mocked for its changes but rather for its lack of change. A long history in France inspiring little to no change within shaped some of the biggest riots in recent memory, particularly in the 1990s and early 2000s. The riots were led by many from the urban renewal projects surrounding the major French cities, focusing on the constant injustice faced by law enforcement and the French elites. France’s reluctance to address systemic issues has long been a source of tension, particularly in its handling of immigrant communities and the banlieues. These areas, often referred to as “zones of neglect,” highlight the failure of successive governments to prioritize integration and equitable resource distribution. While protests and riots have forced public discourse, the slow pace of reform underscores a broader cultural resistance to change.

Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995) stands as one of the most potent cinematic explorations of systemic inequality and urban marginalization in contemporary French history. Set in the banlieues—urban suburbs often plagued by poverty, continuous racial tension, and social neglect—the film captures the anger, disillusionment, and resilience of marginalized communities through the lives of three young men. Inspired by the real-life death of Makomé M’Bowolé, a 17-year-old Zairian immigrant shot in police custody, La Haine channels the volatile energy of a nation grappling with entrenched inequalities. By blending realism with stylistic innovation, Kassovitz crafts a narrative that transcends its immediate historical context, resonating globally as a critique of systemic oppression and institutional failure.

La Haine is not only a cinematic critique of systemic oppression in 1990s France but also a broader cultural artifact that captures the struggles of marginalized youth and their defiance against an indifferent system. The film critiques the cyclical nature of social inequality, emphasizing how the system perpetuates violence, alienation, and despair without offering any real solutions.

The film’s release in the mid-1990s coincided with a period of intense social and political upheaval in France. The banlieues, initially conceived as post-war urban renewal projects, had devolved into symbols of neglect, housing many immigrant families and second-generation citizens who faced daily struggles with unemployment, racial discrimination, and police brutality. The riots that erupted during this time were not isolated events but manifestations of deep-seated frustrations with a government that seemed indifferent to the plight of its underprivileged populations. Kassovitz’s depiction of these struggles not only reflects the social realities of the era but also serves as a searing indictment of systemic injustice, demanding attention to the cyclical nature of oppression and resistance.

This essay examines La Haine through its historical and socio-political lens, analyzing its characters, cinematography, and editing to reveal Kassovitz's layered critique of French society. Furthermore, it situates the film within broader conversations about protest cinema, exploring its connections to global movements against systemic inequality. By delving into the narrative and visual language of La Haine, this analysis seeks to underscore its enduring relevance as a cinematic masterpiece and a poignant reflection of marginalized voices demanding change.

The socio-political tensions depicted in La Haine are deeply rooted in the history of France’s banlieues. Envisioned initially as housing solutions during the post-war reconstruction era, these suburban areas devolved into marginalized enclaves by the late 20th century. Primarily inhabited by immigrants from former French colonies, the banlieues became symbolic of systemic neglect, plagued by high unemployment rates, poor infrastructure, and inadequate public services. These conditions fostered alienation and resentment among their residents, creating a fertile ground for civil unrest.

The death of Makomé M’Bowolé in 1993 serves as a pivotal moment in this history, directly influencing La Haine. M’Bowolé, a 17-year-old Zairian immigrant, was fatally shot while in police custody. He was taken to a police station after they suspected he and his two friends were accomplices in recent burglaries and carjackings. They set free his two friends and began interrogating M’Bowolé, described in court very similarly to that seen in the film, harshly and with force. Unlike the film, M’Bowolé lost his life in this interrogation room after the officer testified he accidentally shot him while trying to scare him into admitting wrongdoing. The officer was apparently unaware the gun was loaded and fired unknowingly. The officer was sentenced to eight years in prison for involuntary homicide.

His death underscored the entrenched issues of police brutality and institutional racism, which Kassovitz sought to highlight in his film. The riots that followed were not isolated incidents but manifestations of decades-long systemic failures, particularly regarding the integration of immigrant populations into French society.

Adding to this volatile environment were the austerity measures implemented by Prime Minister Alain Juppé in the mid-1990s. These policies, which included welfare cutbacks, further alienated already disenfranchised communities. The resultant riots, characterized by clashes with police, arson, and mass protests, became emblematic of the state’s inability—or unwillingness—to address the root causes of social unrest.

The institutional failures depicted in La Haine extend beyond police brutality, reflecting a broader systemic disregard for the banlieues. The education and healthcare systems in these areas often fall short, perpetuating cycles of poverty and exclusion. These conditions mirror the struggles faced by similarly marginalized communities worldwide, making Kassovitz’s critique both locally specific and globally resonant. By situating his characters within this broader context, Kassovitz connects their personal struggles to structural inequities, reinforcing the film’s universal themes of oppression and resistance.

Kassovitz frames La Haine within this historical and political context by using archival footage of riots in the film’s opening sequence to immediately immerse viewers in the charged atmosphere of 1990s France. By doing so, he transforms his narrative into a larger critique of systemic inequality, amplifying the voices of those most affected. The film’s characters and their struggles are microcosms of these larger societal issues, making La Haine both a powerful artistic statement and a historical document.

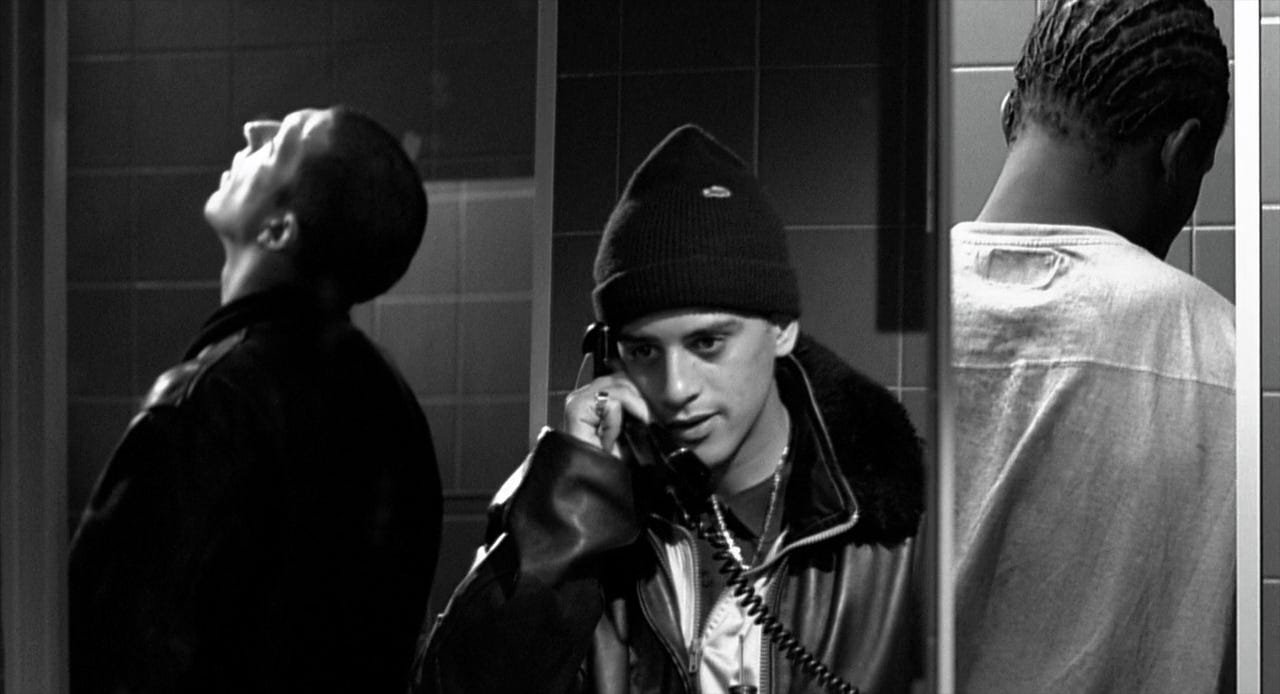

The trio of La Haine—Vinz, Saïd, and Hubert—offers a multidimensional exploration of life in the banlieues, representing different reactions to systemic oppression. Kassovitz opted to use the actors' real names in the film to further capture the realism associated with the riots and unrest.

Vinz, played by now prolific French actor Vincent Cassel, is the most volatile of the group. Consumed by anger and frustration, he embodies the pent-up rage of a generation that feels abandoned by the state. Vinz’s desire for revenge, particularly against law enforcement, symbolizes the destructive potential of unchecked anger. His hallucinations, such as seeing a cow wandering the streets, reflect his internal turmoil and detachment from reality. These moments of surrealism deepen his characterization, portraying him as both a victim of his circumstances and a cautionary figure. His anger and ignorance towards the situation make his death that much more depressing. While his intentions are malicious, his heart stays put on what is right.

Hubert, the eldest and most contemplative, represents resilience and aspiration. An Afro-French boxer with dreams of leaving the banlieues, he seeks to escape the cycle of violence and poverty. Yet his pragmatism often clashes with Vinz’s impulsiveness, creating a tension that mirrors the larger struggles within their community. Hubert’s character reflects the harsh reality that ambition alone is often insufficient to overcome systemic obstacles.

Saïd serves as the group’s comedic mediator. As a North African second-generation immigrant, he navigates the challenges of cultural duality with humor and charm. However, beneath his lighthearted exterior lies a deep frustration with the systemic barriers that define his life. Saïd’s role underscores the emotional toll of being perpetually caught between two worlds. He understands Vinz’s frustration while also siding with Hubert in his desire to leave.

Through these characters, Kassovitz paints a nuanced portrait of the banlieues, exploring themes of identity, solidarity, and resistance. Their dynamic not only drives the narrative but also provides a lens through which audiences can understand the psychological and emotional impact of systemic inequality.

Mathieu Kassovitz’s choice of black-and-white cinematography in La Haine is both a stylistic and thematic decision, stripping Paris of its romanticized image to reveal its harsh realities. This stark aesthetic underscores the socio-economic divide between the banlieues and the iconic city center, contrasting the gritty, graffiti-laden suburbs with the polished architecture of central Paris. The absence of color lends the film a documentary-like authenticity, reinforcing its realism while amplifying its emotional weight.

The film’s camera work plays a critical role in immersing the audience in the characters’ experiences. Handheld shots convey the chaos and instability of the trio’s world, while wide-angle lenses capture the oppressive architecture of the banlieues, emphasizing their confinement. Iconic scenes, such as the rooftop conversations, juxtapose moments of vulnerability with the unrelenting tension of their environment. These visual contrasts mirror the characters’ internal struggles, creating a profoundly empathetic portrayal of their lives.

Kassovitz also employs innovative techniques to highlight the trio’s cyclical existence. For instance, the use of tracking shots conveys a sense of aimlessness as the characters wander through their environment, searching for purpose in a world that offers them none. This approach enhances the film’s narrative and situates it within a broader tradition of protest cinema, drawing comparisons to works like Do the Right Thing and City of God.

La Haine and Do the Right Thing serve to emphasize the socio-political contexts they critique, reflecting the distinct realities of systemic oppression in France and the United States. In contrast to Kassovitz’s black-and-white film, Spike Lee uses vibrant colors and exaggerated camera angles in Do the Right Thing to reflect Brooklyn's heightened racial tensions and cultural vibrancy. The bold reds and yellows in Lee’s film evoke a sense of heat—both literal and metaphorical—underscoring the escalating conflicts between the community and law enforcement.

Though their methods diverge, both directors use cinematography to align viewers with their protagonists' perspectives. Lee’s use of close-ups and Dutch angles amplifies the intensity of interactions, drawing attention to the racial microaggressions that build to the film’s explosive climax. These visual styles distinguish their respective films and reflect the differing societal struggles they portray. While Do the Right Thing captures the immediacy and volatility of racial conflict in America, La Haine employs the slow-burning, cyclical nature of systemic neglect held in France, using its cinematography to evoke a sense of inevitability and entrapment.

The absence of color in La Haine strips the narrative of any romanticism, forcing the audience to confront the stark reality of life in the banlieues. This stylistic choice also unifies the film’s disparate elements, creating a timeless quality that underscores the cyclical nature of the issues it addresses. Black-and-white cinematography has historically been associated with both nostalgia and realism, and Kassovitz uses this duality to reflect the tension between memory and immediacy. The bleak palette mirrors the monotony and despair of the characters’ environment, while the high contrast emphasizes their struggles against a system that offers little visibility or support.

The editing of La Haine embodies the chaos and fragmentation of its characters' lives, blending influences from the French New Wave with contemporary cinematic techniques. Kassovitz’s use of jump cuts disrupts traditional narrative flow, creating a disjointed rhythm that mirrors the instability and unpredictability of the trio’s world. These cuts echo the innovations of Jean-Luc Godard, who popularized the technique in Breathless (1960) to evoke spontaneity and challenge conventional cinematic grammar. However, Kassovitz adapts this approach to a grittier, more grounded aesthetic, aligning the audience with the restless energy of the banlieues.

Rapid montages interspersed throughout the film further heighten this sense of volatility. In moments of tension, such as Vinz’s confrontations with authority, Kassovitz employs quick cuts to compress time and amplify urgency, reminiscent of Sergei Eisenstein’s montage theory. Eisenstein’s influence is particularly evident in La Haine’s juxtaposition of calm and chaos, as seen in sequences where the trio’s fleeting moments of camaraderie are interrupted by violent outbursts. These editing techniques underscore the psychological toll of systemic oppression, forcing the audience to experience the same unease and disorientation that defines the characters’ lives.

Kassovitz’s approach has inspired a wave of contemporary filmmakers, particularly in works that explore marginalized communities. Films like City of God (2002) by Fernando Meirelles and American Honey (2016) by Andrea Arnold adopt similarly frenetic editing styles to reflect the instability and tension of their characters’ lives. At the same time, La Haine draws from earlier films such as Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989), whose dynamic editing and rhythmic pacing similarly emphasize the simmering tensions of urban environments. These cinematic dialogues situate La Haine within a broader tradition of socially conscious filmmaking, where editing serves not just as a narrative device but as a reflection of systemic fractures.

The fragmented editing style reinforces La Haine’s critique of systemic inequality by illustrating the splintered realities of life in the banlieues. Through its disjointed pacing and visual ruptures, the film conveys the inability of its characters to find stability or coherence in a world that denies them both. This technique immerses viewers in the trio’s disorienting experiences and underscores the cyclical nature of their struggles. By aligning form with content, Kassovitz transforms editing into a vehicle for empathy, immersing the audience in the oppressive realities the marginalized face.

Kassovitz’s homage to Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver is most evident in the reimagining of the iconic “You talkin’ to me?” scene, with Vinz mimicking Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle. Like Travis, Vinz channels his frustration and alienation into a performance of hyper-masculinity, using imagined violence to assert control in a world where he feels powerless. This moment encapsulates Vinz’s internal struggle, revealing the fragility beneath his rage. Much like Travis’s descent into vigilantism, Vinz’s bravado is a mask for his vulnerability and disillusionment, highlighting how systemic neglect fosters destructive fantasies of power and retribution.

Vinz’s rage, like Travis’s, is deeply tied to a sense of social and cultural displacement. In Taxi Driver, Travis is a Vietnam War veteran grappling with urban decay and societal alienation, projecting his frustrations onto an unforgiving New York City. Similarly, Vinz is a young Jewish man navigating the banlieues of Paris, shaped by police brutality and systemic inequality. Both characters are products of environments that marginalize and dehumanize them, and their violent fantasies reflect their yearning for significance in a society that denies them agency. Kassovitz’s decision to echo Travis’s monologue through Vinz not only pays tribute to Scorsese but also situates La Haine within a broader cinematic tradition of exploring alienation and identity through rage.

This thematic lineage extends to other films that grapple with similar characters and circumstances. Paul Schrader reimagined Bickle himself in 2017 with First Reformed, this time through Ethan Hawke’s Reverend Toller, whose environmental and existential despair leads to radicalization. Similarly, Todd Phillips Joker (2019) portrays the toxic consequences of isolation and systemic disregard. These films, like La Haine and Taxi Driver, explore how environments of neglect and oppression can ignite a dangerous mix of rage and vulnerability. In all these works, the protagonists’ anger is as much a response to societal failure as it expresses personal pain.

La Haine can also be analyzed through a postcolonial lens, which reveals the lingering impact of France’s colonial history on its treatment of immigrant communities. The film’s portrayal of police brutality and systemic exclusion reflects the structural inequalities that persist in postcolonial societies. The trio’s experiences as young men of Jewish, North African, and African descent underscore the racial and cultural divides that remain unresolved in modern France. Kassovitz avoids overt discussions of ethnicity but uses visual and narrative cues to highlight the characters’ alienation within a society that denies them full inclusion.

Marxist theory also offers insight into the film’s critique of socio-economic disparity. The banlieues, depicted as neglected spaces outside the prosperity of central Paris, symbolize the marginalization of the working class. Kassovitz portrays the police as agents of state control, maintaining the division between the “haves” and the “have-nots.” This dynamic is evident in the antagonistic relationship between the trio and law enforcement, which represents the systemic oppression faced by the banlieues’ residents.

Globally, La Haine resonates as part of a tradition of protest cinema. As discussed earlier, films like City of God and Do the Right Thing are committed to amplifying marginalized communities' voices and exposing the systemic forces perpetuating inequality. Like La Haine, they use visual storytelling and character-driven narratives to challenge dominant power structures and provoke critical reflection among audiences.

The film’s cyclical structure, culminating in its devastating finale, echoes the broader reality of systemic oppression: a perpetuating cycle of violence, alienation, and resistance. By situating La Haine within this global context, it becomes clear that Kassovitz’s work transcends its French setting and addresses universal themes of justice and equity.

Upon its release in 1995, La Haine was met with widespread critical acclaim, earning Kassovitz the Best Director prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Critics lauded the film’s unflinching portrayal of life in the banlieues and its innovative approach to storytelling. Over the years, it has cemented its status as a landmark in French cinema, frequently referenced in discussions about social justice and urban inequality.

The film’s legacy extends beyond its artistic achievements. Its depiction of systemic oppression and police brutality has made it a touchstone for contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter, which confront similar issues of racial and economic injustice. Kassovitz’s decision to focus on the humanity of his characters rather than sensationalize their struggles has ensured the film’s enduring relevance and humanity, even for those blinded by their anger like Vinz.

In academic circles, La Haine continues to be studied as a masterful example of how cinema can critique societal structures. Its influence is evident in subsequent works of French protest cinema, such as Jacques Audiard’s A Prophet and Houda Benyamina’s Divines, which similarly explore themes of marginalization and resistance. The film’s integration of French New Wave techniques with a contemporary narrative style has also inspired filmmakers globally, reinforcing its significance as both an artistic and political statement.

Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine is a haunting reminder of how systemic inequality festers in the shadows of prosperity, breeding cycles of violence and despair that seem impossible to escape. By immersing audiences in the stark realities of life in the banlieues, Kassovitz not only critiques the failures of French society but also forces us to confront the pervasive global forces that marginalize entire communities. The film’s thesis—that oppression and resistance are locked in an endless and devastating cycle—plays out through its characters and their struggles, each trapped in a world that denies them dignity, agency, and opportunity.

The film’s devastating conclusion—a moment of stillness punctuated by a single gunshot—reflects the futility of resistance in the face of an unyielding system. Vinz, Saïd, and Hubert may be fictional characters, but their lives are emblematic of countless real individuals who have suffered under similar circumstances. The banlieues remain neglected, their residents alienated, and the promises of liberté, égalité, and fraternité ring hollow for those left behind by the Republic. Kassovitz’s stark portrayal offers no resolution, no hope for redemption, only the lingering question: how many more lives must be consumed by this cycle before meaningful change is realized?

Even decades after its release, La Haine resonates with an almost prophetic clarity, its relevance only deepened by ongoing global struggles with police brutality, racial injustice, and socio-economic inequality. France’s own recent history, such as the Yellow Vest movement and protests over police misconduct in marginalized communities, could easily provide a contemporary backdrop to Kassovitz’s film. These issues extend beyond France, evoking parallels with American protests like those ignited by the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and countless others. Kassovitz’s sharp critique of systematic oppression serves as a mirror to societies across the globe, illustrating how deeply entrenched inequality continues to breed despair and violence.

One of the most striking aspects of La Haine is its refusal to offer comfort or resolution. While American films like Do the Right Thing left room for ambiguous hope, Kassovitz’s conclusion is chillingly definitive: the system’s failure is total, and its victims are trapped in a cycle of destruction. If Spike Lee’s Brooklyn burns with the heat of unresolved racial tension, Kassovitz’s Paris banlieues smolder in a haze of hopelessness. The universal indictment of systemic failure bridges these cultural divides but also points to stark differences in tone. In America, even at its most cynical, cinema often clings to the myth of the individual as a potential agent of change. In La Haine, even resistance is futile, a futile dance at the edge of a bottomless abyss.

Perhaps what makes La Haine disturbingly relevant is how it lays bare the mechanisms of societal collapse, where neglect, prejudice, and systemic inertia coalesce into inevitable tragedy. The film forces audiences to ask difficult questions: How long can these cycles continue before the breaking point? Is “liberté, égalité, fraternité” just a slogan for those already at the top? For Americans, the questions might take a different form: How often must these stories repeat themselves before the land of opportunity lives up to its name? As Kassovitz leaves us dangling on the precipice, the unspoken warning reverberates across oceans—falling may be universal, but the landing will hurt just as much, no matter where you call home.

Works Cited

“Affaire Makomé M’Bowolé.” Wikipedia, fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affaire_Makomé_M%27Bowolé.

“Amnesty International Report 1996 – France.” Amnesty International, 1996, www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/nws210051996en.pdf.

Arnold, Andrea. American Honey. Film4, 2016.

Audiard, Jacques. A Prophet (Un prophète). UGC Distribution, 2009.

Ben Yamina, Houda. Divines. Netflix, 2016.

Godard, Jean-Luc. Breathless (À bout de souffle). Les Films Impéria, 1960.

Kassovitz, Mathieu. La Haine. Canal+, 1995.

“La Haine – According to the Pole.” According to the Pole, www.accordingtothepole.com/la-haine/.

“La Haine and After: Arts, Politics, and the Banlieue.” The Criterion Collection, www.criterion.com/current/posts/642-la-haine-and-after-arts-politics-and-the-banlieue?srsltid=AfmBOopTSP8-d3yW0zvFUgmUnm9RDttYx4ehiokIuRp00jfjwCEKHuyd.

“La Haine: Kassovitz vs. Sarkozy.” The Criterion Collection, www.criterion.com/current/posts/476-la-haine-kassovitz-vs-sarkozy.

“La Haine: Redefining Rebellion on Screen.” BFI, www.bfi.org.uk/features/la-haine-redefining-rebellion.

Lee, Spike. Do the Right Thing. Universal Pictures, 1989.

Meirelles, Fernando. City of God (Cidade de Deus). Miramax, 2002.

“Off the Radar: La Haine, a Harsh Reality Transcending Time and Place.” Washington Square News, 1 Apr. 2022, nyunews.com/arts/off-the-radar-la-haine-a-harsh-reality-transcending-time-and-place/.

Phillips, Todd. Joker. Warner Bros. Pictures, 2019.

Scorsese, Martin. Taxi Driver. Columbia Pictures, 1976.

Schrader, Paul. First Reformed. A24, 2017.

True Story Award. “La Haine: The Riots and Makomé M’Bowolé.” truestoryaward.org/story/211.

Thank you for reading!